Robert Boettcher, essentially homeless since 2006, has tested many of the public services designed to help people like him. He’s a former resident of Hopeville, the riverfront encampment that became so big that the city scraped it away, citing public health concerns.

He’s lost subsidized apartments. He’s sofa-surfed. Once, he heard a mayor vow to end chronic homelessness in 10 years.

“A lot of them ended up in burned-out buildings,” said Boettcher, 60.

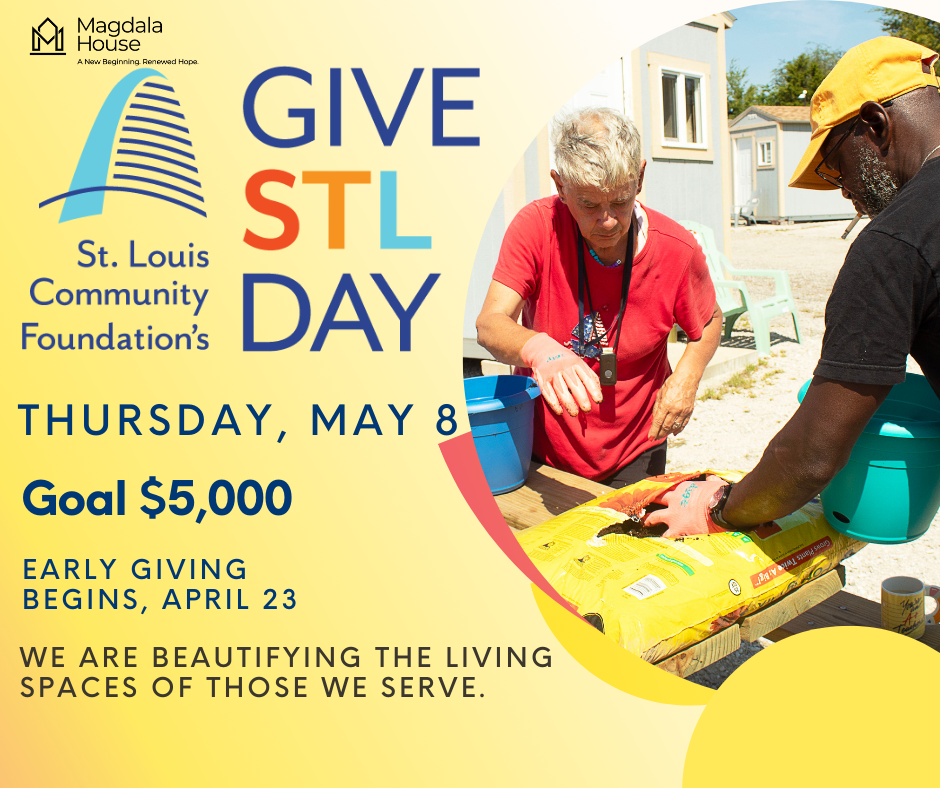

One of the city’s latest efforts to help is the tiny house village, which opened over the winter at a former RV park at 900 North Jefferson Avenue. On Tuesday night, 45 of the 50 one-room houses were booked with about 15 women and 35 men. Several residents, including Boettcher, said they were grateful for their own insulated and secure space.

“This project is working very well, and the city ought to make some more,” he said, adding: “We are a very selected few that got lucky. Probably just the tip of the iceberg.”

The next mayor of St. Louis will have a notable stake in how the homeless are served in the village and on a much bigger scale, especially over the next two years. According to an estimate from Mayor Lyda Krewson’s office, “tens of millions” of dollars in extra federal funding are expected to come to the city for additional homeless services and rental assistance to address continued fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even in normal times, the St. Louis Division of Homeless Services reviews and awards local contracts paid with federal funding. Dozens of nonprofit organizations that serve the homeless in the city apply for it. Collectively, the network of service providers is called the Continuum of Care.

At times, the relationship between the city and the Continuum of Care has been strained from disagreements over how to best serve the homeless, like when the city quickly cleared a homeless encampment on Market Street, across from City Hall.